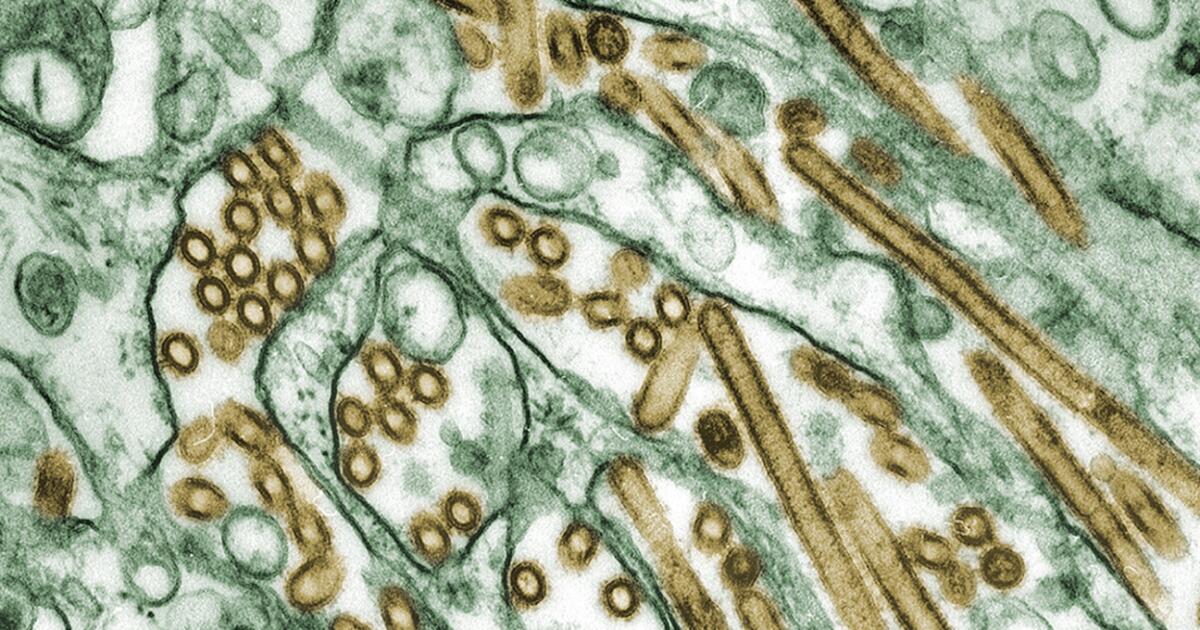

Flu season is over, but there is a viral surge in California wastewater. Is it avian flu?

An unusual surge in flu viruses detected at wastewater treatment plants in California and other parts of the country is raising concerns among some experts that H5N1 bird flu may be spreading farther and faster than health officers initially thought.

In the last several weeks, wastewater surveillance at 59 of 190 U.S. municipal and regional sewage plants has revealed an out-of-season spike in influenza A flu viruses — a category that also includes H5N1.

The testing — which is intended to monitor the prevalence of “normal” flu viruses that affect humans — has also shown a moderate to high upward trend at 40 sites across California, including San Francisco, Oakland and San Diego. Almost every city tested in the Bay Area shows moderate to high increases of type A viruses.

Alexandria Boehm, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University and principal investigator and program director for WastewaterSCAN — an infectious disease monitoring network run by researchers at labs at Stanford, Emory University and Alphabet Inc.’s life sciences research organization — was careful to note that an increase in human influenza A virus in wastewater does not necessarily mean that bird flu is present. However, it does raise that question.

Some experts fear that H5N1 is essentially flying under the radar, spreading undetected among birds, livestock and possibly humans, and say the increase in positive test results at sewage plants could be an indication of this. They worry that if the virus continues to spread among livestock, there is a greater risk that the virus will mutate in a way that makes it more of a threat to humans.

“There seems to be an outbreak throughout California, and, as far as I know, they haven’t reported any infected cows in that state yet,” said Marc Johnson, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri, referring to the cluster of yellow and orange dots on the WastewaterSCAN map.

Johnson is among a number of experts urging the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to test specifically for H5N1 and to make those results public.

Avian flu has been positively identified in 42 cattle herds across nine states, suggesting its spread has been somewhat limited. However, the wastewater surveillance testing shows a surge in flu viruses in 23 states, including some that have seen outbreaks at dairy farms.

Boehm said they have testing in 41 states; not all states participate in the WastewaterSCAN academic program.

So far, there have been no reported herds infected in California, which is the nation’s largest milk producer. The state supplies roughly 20% of the nation’s milk, is home to about 1,300 dairy farms and has an estimated 1.7 million dairy cows.

Most human influenza viruses are seasonal, arriving in the fall and disappearing by early spring. Therefore, finding the virus in wastewater during these periods is “what we’d expect when you have more influenza cases in hospitals, more hospitalizations, more emergency department visits,” said Boehm, the Stanford professor.

“What we’ve noticed this year is that after influenza season, there was a fraction of the wastewater treatment plants we survey, that when we looked closely at them at the end of April, there were increases,” she said, including some really “obvious” ones such as two in Amarillo, Texas, where they knew H5N1 had been detected in dairy cattle nearby.

The team contacted the local public health department and got permission to test for bird flu virus. It was a match. So, too, was the wastewater from a Dallas plant.

Boehm said the finding suggests that the increases they are observing at these other sites — 59 of the 190 that they track — might also be avian flu.

She said the sites they are looking at deal with municipal, not agricultural, wastewater, “so they’re not getting farm runoff.”

Instead, at least in the case of Amarillo, it’s probably from permitted dairy processing centers — “places that were making cheese or yogurt … that had a permit to discharge into the waste stream.”

What’s causing the upward trend at other sites is not clear. But if the uptick is the result of bird-flu infected dairy getting into the municipal waste stream — and since milk is generally trucked from dairies to processing centers — the source of infection is probably not too far away. These positive sites provide a geographical flag for public health officials to take a closer look. (The CDC has said that pasteurization of milk kills the virus.)

Johnson, who developed an H5N1 assay to test wastewater in Missouri, was asked by federal officials to withhold using the test for fear it could “add to the confusion.”

“This is the perfect example of why it makes sense,” to test specifically for H5N1 in wastewater, he said. “Because then you would know whether this is really H5, because no matter where it’s coming from, if it’s showing up in California, that’s saying something.”

Johnson said if the tests show it’s H5N1, there could be infected cows in California.

The CDC monitors roughly 600 sites, and “what we are seeing is very localized increases that are out of season for seasonal flu,” said Amy Kirby, senior service fellow in the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch at the CDC.

She said that when they see those increases, they go in for a deeper look.

In an interview on Friday, she said she was unable to provide more information, because the agency was “finalizing that data and checking it to make sure it’s correct.”

Tom Skinner, a CDC spokesman, said that data will be available on the agency’s avian flu dashboard Tuesday. He said in an email that some of the sites they’ve looked at are in California, but declined to add more information until after the agency has posted its own dashboard.

To some researchers, the spike in viruses found in wastewater is a call to action.

“I think we have a good opportunity here to kind of prepare in case of the worst case scenario,” said John Dennehy, a virologist at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. “Now, we know it’s there. We know it hasn’t jumped into humans yet, but can we muster the public health infrastructure to prepare in advance if this should jump over from cows into humans? Whether it is coming from milk? Or some other means?”

It was in Dennehy’s laboratory that New York City’s coronavirus wastewater test was developed.

Dennehy and his colleague, Denis Nash — distinguished professor of epidemiology and executive director of City University of New York’s Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health — said it’s only been since about 2020 that researchers have been using wastewater surveillance to monitor public health.

It’s now seen as a “first line” method of surveillance — gathering information about outbreaks of flu, polio, rhinoviruses and other diseases. But it’s largely been driven by academics and local agencies.

In the case of bird flu, a more centralized, or organized, system of monitoring and messaging is required, they said.

“I think the important thing here is that CDC should be describing what’s going on with influenza A in wastewater,” said Nash. “It’s great that academics are doing it. We all are stepping in because it often seems like the government is a little bit delayed or just not engaged. But really, the CDC should be leading this.”

Calls to wastewater treatment centers in Santa Cruz and Oakland went unreturned. A query to an official at UC Davis’ wastewater treatment center, which shows an uptick, also went unanswered.